Food

The War brutally intervened into the lives of inhabitants of the Monarchy in all walks of life. Already in the first year of the War, there was a huge food crisis, drastically changing dietary habits and sometimes causing starvation. The highest prices for wheat, flour and other foods were set in Austria-Hungary already in the middle of 1914. Nevertheless, the prices increased ten- to fifteenfold by the end of the War.

The general reduction and lack of food reserves became critical in the winter of 1915. The calls to save food, firewood, salt, oil, flour and bread became a daily companion to war. The sale of important foods and bread soon became rationed. Planned saving and reduction of food quantity were followed by various censuses and requisitions. Markets, shops and butchers became more expensive and emptier. Wheat flour was no longer sold. Because of many additives, bread became more indigestible, ‘flat and crumbly’, called war bread, ‘Kriegsbrot’, by the people.

1916 marks one of the peaks of the food crisis. Starvation was especially prevalent in lower urban classes. People could get less and less for money and more and more for material exchange. There was very little petroleum and tobacco. More and more industrial substitutes were sold for foods. Another characteristics of life during the war were every-day calls to save and collect edible fruits. In the very beginning of the war, Austria-Hungary militarized all army-related economic and food capabilities. According to the Law of War Supply from 1912, factories and employees producing materials needed by the Army were subject to strict military control and appropriate legislation was passed to control working hours. Employees were under the jurisdiction of court martials.

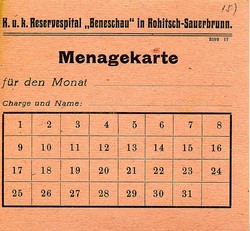

State government started to intervene increasingly into the economy, creating specific administrations, such as an administration for resources with the intention to implement an effective centrally-led military economy. Following the German example, Austria-Hungary established a series of centres to procure and distribute consumer goods: Food, Feed and Cotton Centre, Wool and Metal Centre, Military Wheat-Traffic Institution and others. At the end of the War, more than 90 such centres were operating, together with widely spread military bureaucracy.

An important cause of the growing crisis and economic failure was the limitation of international. The lack of food was no better even in military units towards the end of the War. The food crisis that affected both Armies entrenched in the swampy regions by the Piava river reached its peak in March, 1918, best illustrated in the fact that ‘the average body weight of soldiers fell to 50 kg’.

Marko Štepec, M.A., National Museum of Contemporary History